|

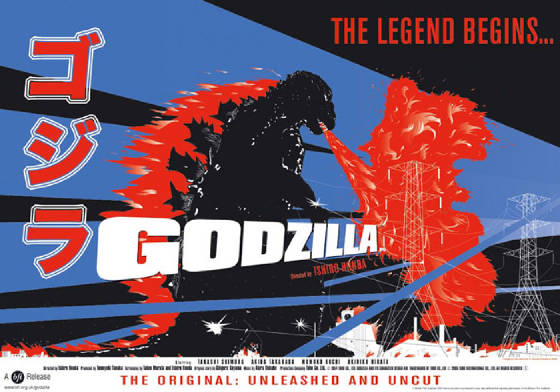

(1954, directed by Ishiro Honda)

- inducted 2017 –

“As a response to the national tragedies of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, perhaps it’s not surprising that, unlike the

countless sequels, remakes, cartoons and toys that came after, Ishiro Honda’s Godzilla is… not a lot of

fun. From the perspective of an American 2017 viewer, raised in the shadow of blockbuster spectacles, it does everything wrong.

There are characters — the professor who wants to study the beast; his daughter; the man she loves; the scientist she’s

engaged to — but we’re never asked to be too invested in them. There’s a love triangle, but in the non-Euclidean

geometry of the film, it’s missing a side. There is no hero with a personal connection with the creature who must overcome

personal difficulties in order to save the day — or rather, there is, but the film undermines this seemingly-bedrock

story construction. No quips, no jokes, lest anyone on either side of the screen crack a smile.

“Directorially, the shots are uninflected, even a little prosaic, nearly always with a Mametian practicality. Godzilla’s

attacks are never played for excitement, only terror, but even then, because the static shots are descriptive rather than

immersive, that terror can seem more intellectualized than felt. Compared to something like Cloverfield, with its mobile

first-person camera that infuses every moment with a hot, smeary, panicky desperation, Godzilla runs cool and crisp.

* * *

“Here’s the paradox, though, one that is not unique to Godzilla but always a trip nonetheless: all these

choices and techniques, designed to keep the viewer at an emotional remove, ends up imbuing the film with a torrent of emotion.

Honda’s camera is passionless and unblinking as it surveys a hospital ward full of Godzilla’s victims, some having

lost their families. When a young island boy loses his family, it holds still on his screaming face, observant and non-judgmental.

The film trusts us to be human in our response, because goosing the viewer with emotional tricks wouldn’t just be cheating.

It would cheapen everything Godzilla has to say. Because what it wants is for the audience to not only take in what

a nuclear world means, but also, what it means to have nuclear weapons.

“There are three brilliant moments in Godzilla. The first is when the film gives a Japanese scientist what is

essentially a nuclear bomb (here, an ‘oxygen destroyer’). The men and women who made the film had every reason

to be angry, and to feel victimized by the U.S. government; yet they slid these emotions off the table and placed themselves,

via the scientist, in the role of the victimizer. The film asks, pointedly and without emotion, what responsibility does having

this power entail?

* * *

“And yet, all of this builds towards something beyond a well-earned fear of a nuclear present and future, beyond a cathartic

attempt to come to terms with atrocity. It says: life is fucking fragile.

“A tank of fish is reduced to skeletons in seconds. A house collapses with no warning, killing the family inside. A

doctor attends to a child exposed to the monster’s radiation, and he shakes his head — she won’t make it.

A woman, in the middle of the inferno, holds her children close and promises they’ll see their father soon.

“And it’s not just the people — the physical objects succumb as well. City buildings crumble. Electrical

towers melt. Trains turn into breakable toys. Ships burst into flame and sink into the abyss.

“Life is fucking fragile.

“And here’s the movie’s second brilliant moment: Godzilla is fragile, too. The creature that has been killing

thousands, irradiating thousands more, and reducing Tokyo to rubble. Impervious to machine guns and missiles: fragile. Two

men are sent into the deep to destroy Godzilla with the oxygen destroyer. It could be a heroic moment, but the film in no

way endorses it as such. The music, instead of being rousing, is mournful, elegiac. Underwater, Godzilla turns his head when

the men land, like he’s heard them, like he knows what’s going to happen. And when the end comes, it’s agonizing

to watch. Godzilla dies, slowly, painfully.

“Life is fucking fragile. And with fragility comes compassion.

“And now, as I write this, the President of the United States of America has, on the anniversary of 35,000 people dying

in Nagasaki, threatened another country with, and I fucking quote, ‘[F]ire and fury like the world has never seen.’

But we have seen it, you coddled ignoramus. We have the footage, we have the accounts. And we know it doesn’t do anything

except magnify misery in the world. But to understand that, you have to understand fragility; and to understand that, you

have to have something other than a gaping void where a soul normally is.

* * *

“The third brilliant moment. That’s when the scientist decides that he has a responsiiblity to not only destroy

his work in order to keep the bomb away from those who would use it, but he kill himself to seal that knowledge away forever.

Because life is fucking fragile, a weapon, that can vaporize entire populations, that trades on that fragility, is

abhorrent.

“Perhaps I was wrong when I said the film wasn’t angry. The message to American scientists is a clear middle

finger: ‘You should’ve just killed yourselves.’ It’s a message that the robber barons, white supremacists,

nihilists, and general incompetents that currently occupy the White House — the ones contemplating the unthinkable —

should maybe consider.”

~ Kent M. Beeson

|