|

(1902, directed by Georges Méliès)

- inducted 2018 –

“Several years ago, just before her ninth birthday, my daughter got her first taste of pioneering filmmaker George

Méliès on the big screen—his mind-boggling short Un homme de têtes (1898), also known as Four Heads are Better

Than One, in which an illusionist decapitates himself three times and performs a song with the detached noggins, and,

of course, his most famous leap of imagination, Le voyage dans da lune (A Voyage to the Moon).

“She was well familiar with modern movie trickery by then, of course, but only just beginning to dip her toes into the

vast sea of film history, so she was perhaps more open than most kids her age to the prospect of sitting through what even

many adults might consider merely a museum piece. I was thrilled with the excitement of her response to Méliès’ work,

and whenever I see A Voyage to the Moon I think of how receptive she was, and what it must have been like for people

in 1902 to see this sort of magic, to see things they’d never seen, unfold before them through this magical new medium.

Audiences who were among the first to see Méliès’ masterpiece couldn’t help but have marveled at not only the

whimsical strangeness of what they were seeing, but also at how they could have been seeing it.

“I often suspect (fear) that the overreliance on CGI in modern filmmaking (and our passive acceptance of it) has led

to a conspicuous absence of wonder and speculative creativity, both in filmmakers and in audiences. But if there is any evidence

in film history of imagination as pure creative fuel, as a ship capable of transporting audiences anywhere he wanted them

to go, Méliès, especially in A Voyage to the Moon, provide it without a moment’s hesitation, with the daring

of true visionary inspiration. And the visions contained within it are many, especially for a film only 14 minutes long--

the multi-leveled backdrops which move and shift with dreamlike fluidity, constantly revealing surprises, like the most elaborate

pop-up, pull-tab storybook conceivable; the impossible feats of travel achieved by a space capsule shot out of a cannon, a

great interstellar bullet aimed directly (through a marvelous perspective rendering) straight at its lunar target; the chaotic

scrambling of the film’s characters as they eagerly anticipate their journey to the moon, and then tumble madly from

danger at the hands of the royal guard of moon-dwelling warriors they find inhabiting the surface; the incredible sight of

one of these warriors jumping on the back of the ship just as it sails off a cliff toward the ocean below, where it will somehow

find the power to propel its passengers back to terrestrial safety; and of course, the eerie beauty of Méliès’ firmament

personified—the stars and planets above all fixed with the faces of those the travelers have left behind, calling them

back with memory but also encouraging their hopeful exploration.

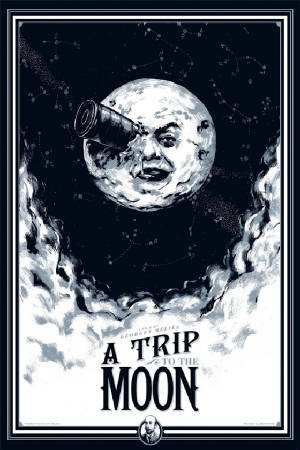

“One of the most famous images in film history is, of course, a similar personification—the moon itself seen as

the ship approaches, the camera moving in slowly, reveals the story-time mythology of the Man in the Moon to be all too true.

And when our intrepid travelers land on the surface, Méliès renders the event spectacularly, burying the ship in the Moon’s

right eye, a great glob of (what else?) cheese erupting from the violated socket.

“Perhaps the most potent magic of A Voyage to the Moon, certainly its greatest legacy for modern viewers, may

be how effortlessly it transports the receptive audience back to a state where everything about the medium of motion pictures

was new, marvelous, frightening, too much to process rationally. It leaves us in a mode of receptivity to the gorgeous, lunatic

whims of its creator, to the true imaginative magic of seeing and believing, that should be the envy of anyone who, after

having seen it, decides to try and tell a story on film. To be transported so wholly into the mind and spirit of a filmmaker

is a true rarity, and Méliès set the bar very high very early. It’s no wonder that the trajectory of movie history,

and its relentless pursuit of ever-greater levels of spectacle, of ‘realism,’ has had most filmmakers hightailing

it in the opposite direction from Méliès’ stylistic marvel ever since. After all, such originality of creative inspiration,

fabulous human ingenuity facilitated by emerging technology, can’t be chased or duplicated; it is, as A Voyage to

the Moon has testified for 116 years, a moonscape of never-before-seen sights all its own.”

~ Dennis Cozzalio

|